This is the story of how, long ago, a book and a drawing project led to a journey to a faraway land.

The Book

The book at the centre of this story is “Krabat”, written in 1971 by the German author Otfried Preußler. The book is based on an old Sorbian legend about the sorcerer Krabat. It is set in the Lausitz area of Germany, in particular the ancient village of Schwarzkollm where Krabat is said to have learned his magic powers. The story plays in and around Schwarzkollm during the Great Northern War (Große Nordische Krieg, 1700-1721) and focuses on Krabat’s youth as an apprentice (Mühlknappe, literally “mill boy”) in the Black Mill in the Kosel moor, where he learns the arts of both miller and sorcerer. It is a story about magic, good and evil, power and love. What appealed to me in particular is the realism of the setting, and the importance put on rituals, both magical and religious, and the passage of time marked by the seasons.

The Story

The book covers three years in Krabat’s life, starting when he is a fourteen-year-old orphan beggar boy. A voice in a dream tells him to go to the mill in Schwarzkollm. It turns out that the mill is a school of black magic, and he becomes one of the twelve apprentices, and gets lessons from a magic book called the Koraktor. The other apprentices that I will mention further on are Tonda, the head journeyman in the first year; Hanzo, the head journeyman after that; Staschko; Juro; Merten; and Lobosch, who becomes the twelfth apprentice at the start of the third year.

Krabat gradually finds out that learning black magic comes at a cost. The Master of the Black Mill has a pact with the “man with the cockerel feather”, also called “Goodman” (“Gevatter” in German, which is close in meaning to Godfather), who visits the mill with his heavy black cart at every new moon. Although the mill operates as a normal mill, it never does any trade, so its only real purpose is to grind the loads which this Goodman brings. As part of the pact, every year, in the last night of the year, one of the apprentices has to die. Tonda dies at the end of the first year. Merten’s brother Michal dies at the end of the second year, after which Merten first tries to run away but fails, and then tries to kill himself, but also fails. The Master is not just master of the mill, but decides who lives or dies, and who can leave the mill.

When Krabat realises this, he starts looking for a way out. Meanwhile, he has fallen in love with a girl from the village. In the book, she is only refered to as the “Kantorka”, a Sorb word for the girl who leads in the singing, in particular on the Easter night. Krabat fell in love with her when he heard her singing on the Easter night of his first year. Tonda has warned Krabat that if he ever has a girl, he must keep this a secret from the Master, and never reveal her name or the girl will die. This has happened to his girl, Worschula. Krabat is careful but the Master still becomes suspicious. But because Krabat does not know the girl’s name, he can’t give it away.

Juro pretends to be stupid but isn’t. He is the only one of the apprentices who has read the Koraktor. He becomes Krabat’s ally and tells him about the only way to break the Master’s hold: if the girl of an apprentice will come on New Year’s Eve and ask for his release, she will have to pass a test. If she does pass, they will all be free and the Master will die. The Koraktor only says that the test is to recognise her love amongst the twelve apprentices. However, the Master is a master of interpretation of this test, and no girl has ever been able to pass it.

The Project

I don’t remember when I first read the book; it must have been some time in the second half of the 1980s. But it made a strong impression on me, and I re-read it many, many times. In the meanwhile I had taken up drawing, and I thought it would be an interesting project to create a series of illustrations of my favourite novel.

Then one day I discovered Schwarzkollm in an atlas, and realised it was a real place, and that I maybe could even go there. So the plan was born for a journey to Schwarzkollm, to do research for my illustrations.

The Reality

However, I had to postpone my plan a bit for various reasons, the most important one being that Schwarzkollm was in Eastern Germany, which was behind the Iron Curtain until 1990.

This is now old history, but a brief summary will help with the rest of the story. After the Second World War, Germany was partitioned in West Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland) and East Germany (Deutsche Demokratische Republik, DDR). As East Germany was part of the Eastern Bloc, a fortified frontier (with actual fences, walls, minefields, and watchtowers) was erected between the two countries, called the “Iron Curtain”. Travel across this border was severely restricted. It is unlikely that I would have been allowed to travel to Schwarzkollm on my own. The DDR was a socialist state under strong influence of the Soviet Union.

Then in 1990 the Iron Curtain disappeared and East and West Germany were reunited. At that time however, I was too busy studying to pursue my project. It wasn’t until 1994 that I was ready to realise my plan.

But in 1994 communication was very different from now. The Internet was still in its infancy. TIME magazine did a cover story on it, but it was so unfamiliar that they had to begin by explaining what it was: “the world’s largest computer network and the nearest thing to a working prototype of the information superhighway”. So I could not use the internet to establish contact with someone in Schwarzkollm. And as I did not know any names, I could not telephone either. That would have been difficult anyway as I didn’t speak German. And as I learnt later, almost nobody in that part of Germany could phone internationally, unless they had a satellite phone.

The Contact

So I took a postal distance learning course in German, and managed to write a letter which I simply addressed to “ The mayor of Schwarzkollm”, explaining that I would like to visit the village for a week to do research for an illustration project about Krabat. This was in November of 1994.

In January 1995, against my expectations (if not my hopes), a reply arrived! The Bürgermeisterin (mayor) of Schwarzkollm, Frau Winzer, wrote to say that she welcomed me to the village and would arrange for me to stay with someone locally. Some time later, another letter arrived from a certain Herr Blazejczyk, who explained that his family was living in a large new-built house and that it would be a pleasure to let me and my partner stay with them for a week in May 1995, free of charge. They would also meet us at the railway station, if I could write them back once I knew the arrival time of the train. Because of course this was before the mobile phone, so we could not text or phone them from the train.

The Journey

Because naturally, the way to travel to Schwarzkollm from my home in Belgium, about a thousand kilometres, was by train. Air travel was much less common in those days, and we were already ecologically aware. But again, there was no internet, so booking tickets was done at a dedicated ticket window for international travel. There, they explained to us that yes, they could sell us a ticket, but unfortunately not all the way: it was not possible to get a ticket for the part of the journey that was in ex-East Germany. But instead they could provide us with a letter of transit signed and stamped by a high-ranking official of the Deutsche Bahn, the German national railways.

I don’t remember the details, but we must have left our departure station of Gent Sint-Pieters very early, because when we finally arrived, it was still light. We changed onto the Germain railways at Aachen, and then a few times more. And it worked! Whenever we showed the letter of transit, the train guard read it, gave it back to us with a mystified look, and left us alone. I remember in particular the journey along the Rhine, which I’ve always loved. And I remember that we changed onto the final, local train in a virtually deserted, almost derelict station, which might have been Falkenberg/Elster. I also remember the look of that train: a Spartan, brown-liveried ex-DDR train.

When we arrived at Schwarzkollm station, Herr Blazejczyk and Frau Winzer were both waiting for us on the platform. The first thing they asked was “Was the train punctual?”

As indeed it was, every leg of the journey had been perfectly on time.

The Stay

Herr Blazejczyk took us to his house where we met his wife, Frau Blazejczyk. Both Herr and Frau Blazejczyk spoke German and English, which was a relief (as our German was still very poor). It was also at that time a rare thing in ex-East Germany: the second language that most people there learned at school was of course Russian. English or French were optional third languages.

We had very interesting discussions with them. I remember in particular a discussion about Documenta IX. Documenta is an exhibition of contemporary art which takes place every five years in Kassel. The most recent one at that time, Documenta IX, took place in 1992 and was curated by a Flemish artistic director, Jan Hoet, who was the founder and director of the Municipal Museum for Contemporary Art in my home town Ghent.

We also talked about the how it was under Communism, which was by far not as universally bleak as we had assumed, but economically not sustainable. And about the effects of the reunification, which also were not all positive.

And with Herr Blazejczyk in particular, I talked about beer. We had brought some typical Belgian beers as a gift, and they were in awe at their strength (“Aber das kann man doch nicht trinken!”, “But you can’t drink that!”).

The Village

Schwarzkollm is a small village, about five hundred people at that time, essentially a single main street. There was a watermill, which has in the meanwhile been rebuilt an is now a major tourist attraction. In 2005 the book was turned into a successful film and that has led to a huge increase in visitors to the mill. But when we were there, it was old and not well maintained, and very much what I was looking for as inspiration.

The village lies in an area called Oberlausitz (Upper Lusatia) where a Slavic ethnic group called the Sorbs (Sorben) lives. They speak a Slavic language called Sorbian or Wendish, are predominantly Catholic and have their own cultural traditions. In Sorbian, the name of the village is Čorny Chołmc.

It was amazing to be in this very place where to book was set. Because it was such a small place, it was easy to get around. The people were very hospitable and very nice to us and helped us in many ways. We also had the use of bicycles to explore the surrounding area, in particular the Kosel moor. One of those visits took us to a pottery where the potter (Töpfer) showed us his art and we bought two simple mugs with the traditional peacock’s eye decoration which is typical for that region. We still call them the “Töpferpotjes” (“potje” means small mug in Dutch).

The Research

My main purpose was of course to collect material for my illustrations. By coincidence, the year before Schwarzkollm had celebrated its 600th anniversary. As a result, a lot of promotion material and a special commemorative book had been published, so I got a wealth of printed material, historical information and pictures.

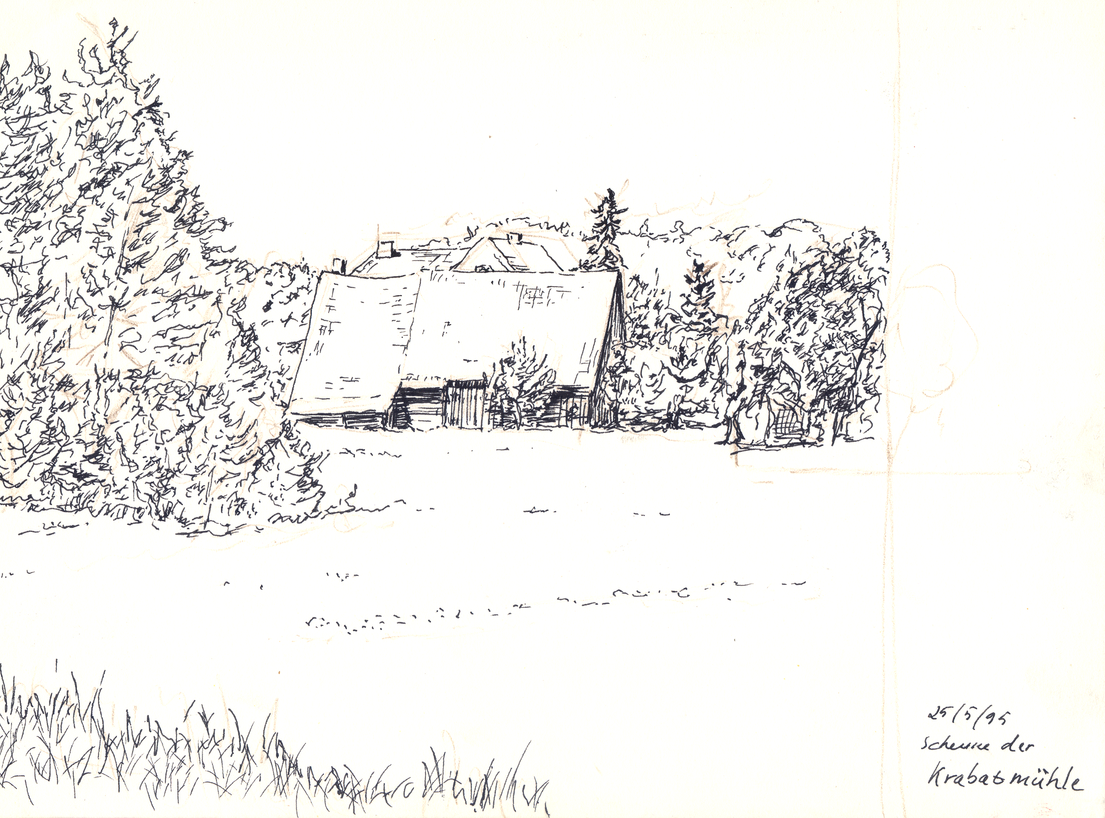

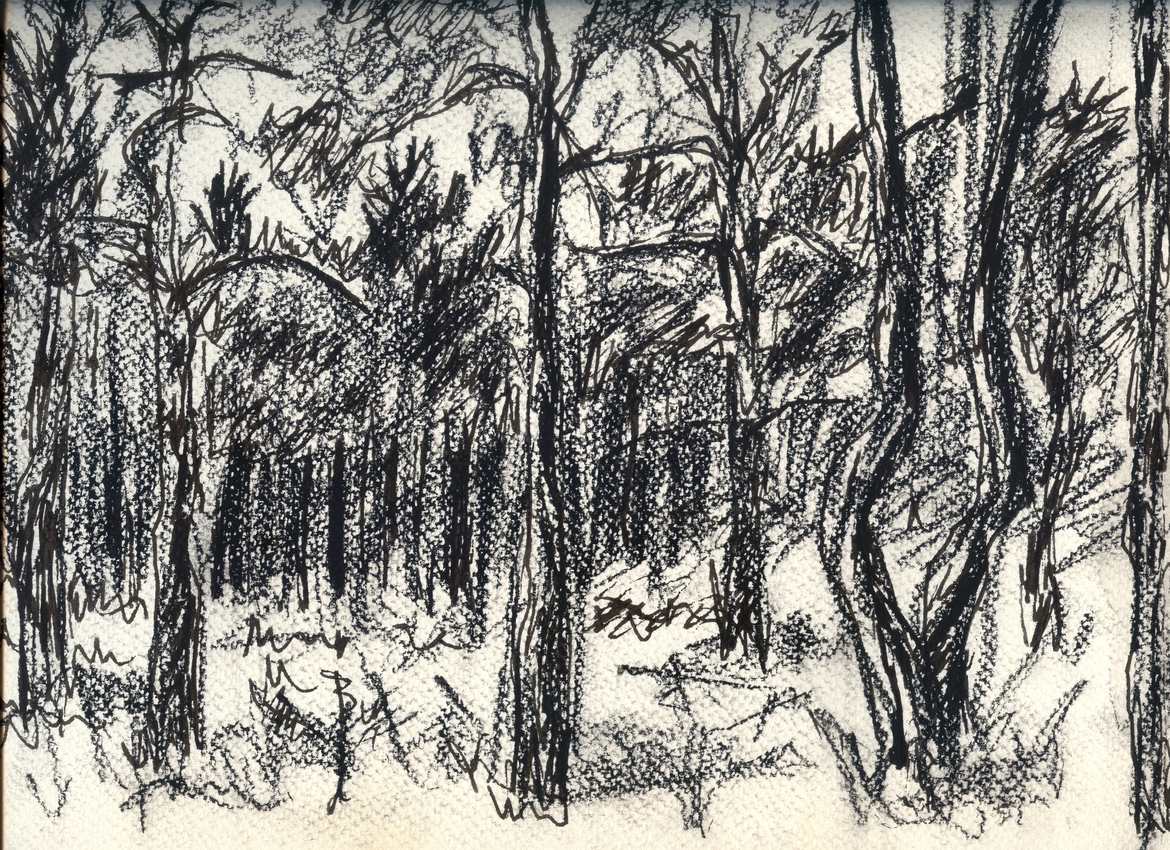

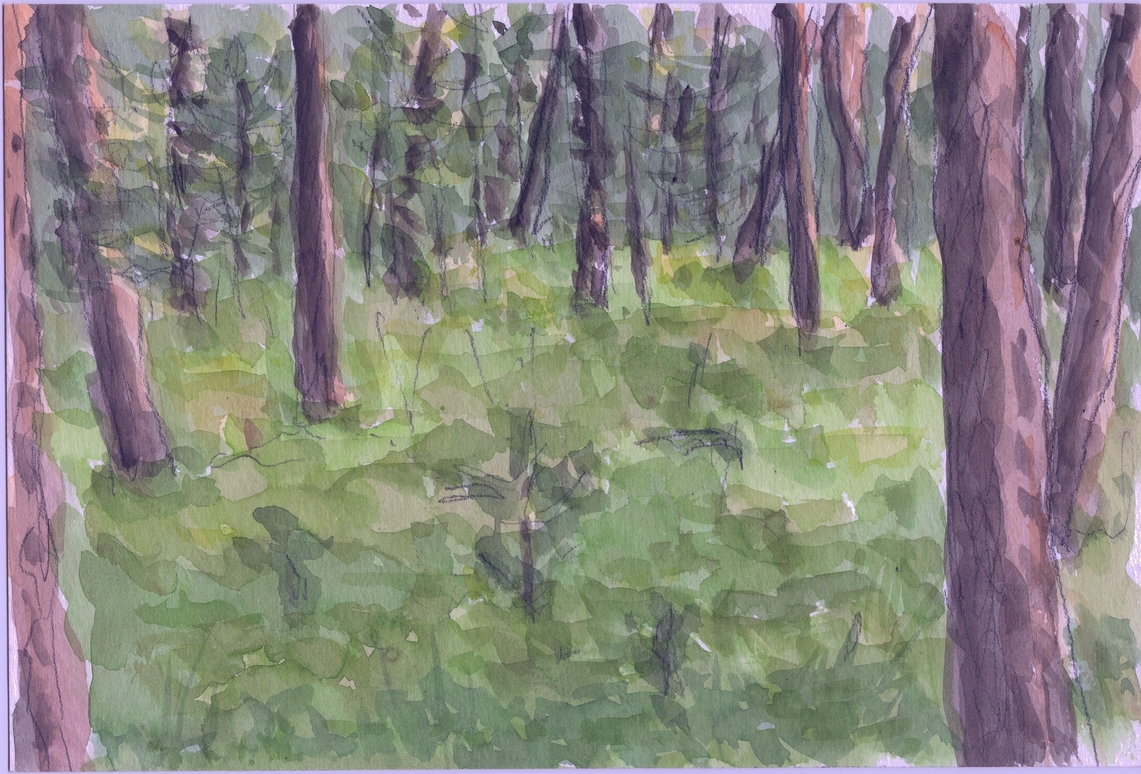

Still, the most effective way is to make sketches so I walked around with my drawing materials and made lots of sketches. Luckily the weather was perfect.

The Oberlausitz landscape is one of gentle rolling hills, and quite sparsely populated (or at least it was in 1995). This view of the village is representative for the area.

The church of Schwarzkollm was painted a peculiar green that many people in the village did not like because it looked “wie eine Rüssenkazerne”, like a Russian barracks.

It looks nice in black and white though.

I made some sketches of old buildings as well, like this barn which according to my annotation is that of the Krabat-mill.

I also made sketches of the forest and moor surrounding the village. In retrospect it is interesting to see how similar this is to the Scottish moorland, but of course I did not know this at the time.

I remember another random connection to Scotland though: for some reason, a farmer from the village had a herd of Highland cattle, the Scottish breed with the long hair and huge horns.

The Work

I had already made a selection of scenes of the book I wanted to illustrate, so most of the sketches were made with these in mind. On my return I made a final selection of nine illustrations. In the end it probably does not seem like a lot of research went into each drawing, but I know I could never have made the illustrations the way they are without the visit.

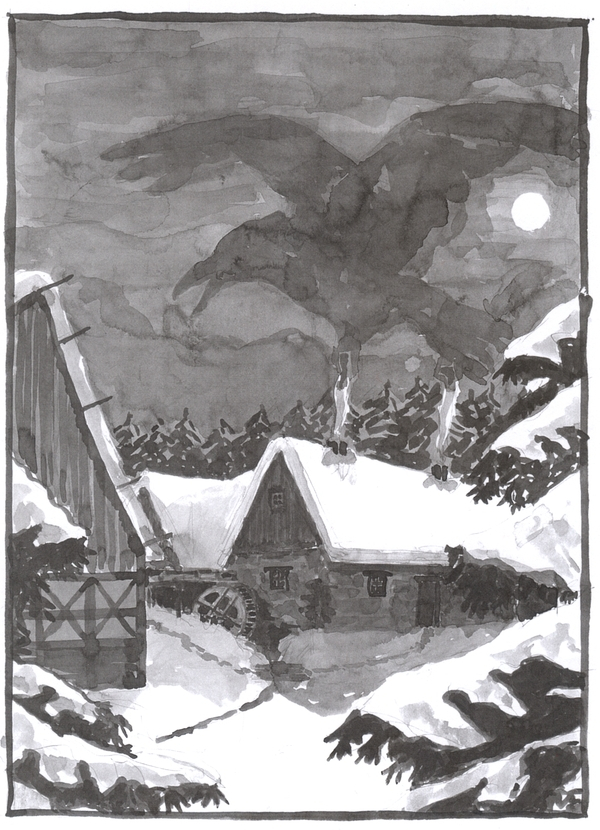

I used a Chinese ink stone and stick and Chinese brushes to make the illustrations. The paper is Steinbach satin, 250 g/m², a nice smooth paper that absorbs the ink very nicely.

Here are the illustrations, with the part of the book they illustrate. The English text is my translation from the Dutch version, not the published English translation.

The first illustration is of the scene when Krabat arrives at the Black Mill, to which he is called by a voice in his dreams. It is in the days between New Year and Epiphany.

Like a blind man in a fog, for a while Krabat groped his way through the forest by touch. Then he suddenly found himself in a clearing. At the same time, the moon broke through and suddenly cast everything in a cold light.

There stood the mill. Dark and threatening it lay in the snow, like a strong, dangerous animal eyeing its prey.

The raven in the sky is a reference to the transformation of the apprentices into ravens whenever they get a class in magic. On the crest of Schwarzkollm, Krabat is shown half-transformed, flying with raven’s wings.

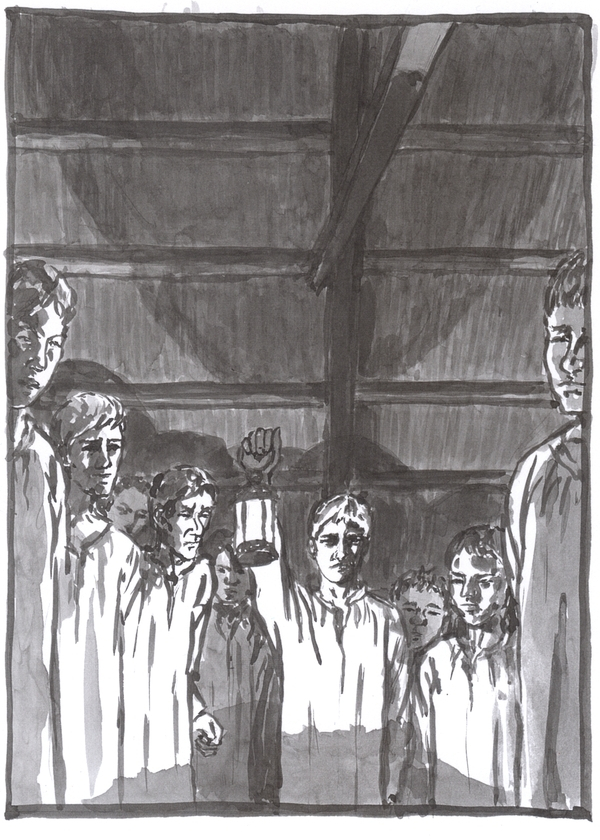

The second illustration is of the scene where Krabat has gone to sleep, that same night, after the miller has accepted him as an apprentice. He is woken up in the middle of the night, and the apprentices are standing all around him in their nightshirts.

The attic reverberated to the stomping and rumbling of the mill. Just as well that Krabat was dog tired: he fell asleep like a log as soon as he lay down — and he slept until a ray of light woke him.

Krabat sat up and froze with fright. Eleven white appearances stood at his bed and looked down on him; eleven white figures with white hands and white faces.

"Who are you?" he asked fearfully.

"We are what you will become," said one of the ghosts. "But we won't do anything to you," added a second one. "We're just miller's apprentices."

"Are there eleven of you?"

"You are the twelfth."

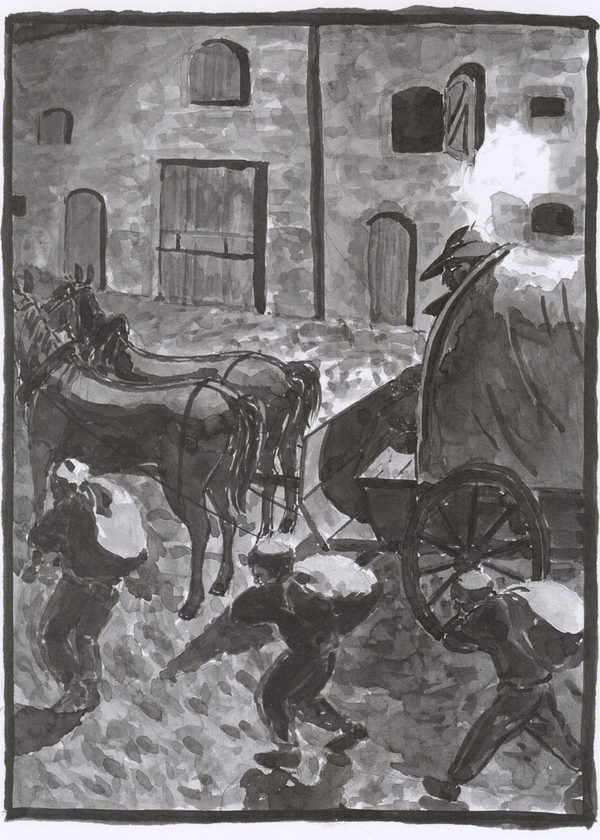

Then there is the scene when the sinister “man with the cockerel feather” comes and the apprentices have to work all night.

Was the mill then really on fire?

Krabat was suddenly wide awake and pulled open the window. He leaned out and saw in the mill yard a heavily loaded flat cart, with a sturdy cover, blackened by rain, with a team of six pitch black horses. Someone sat on the box, with his collar up and his hat drawn low over his face; he was also entirely clad in black. Only the cockerel feather in his hat was bright red and waved in the wind; it seemed like a tongue of fire, waxing fiercely and then shrinking, as if on the verge of going out. The gleam was so strong that it bathed the whole yard in a flickering light.

The apprentices ran back and forth between the mill and the cart; they unloaded sacks which they hauled to the mill room and returned for more. Everything happened in dead silence but with a feverish haste.

What I consider a key scene is when Tonda gives his special knife to Krabat. Tonda is called the “meesterknecht” in the Dutch translation, in German “Altgesell”. In the English translation the word used is “head journeyman” which I feel does not have quite the same connotation of experience and seniority.

The 'barren plane' was a square clearing, barely larger than a threshing floor, surrounded by a few stunted pines. In the gloaming the boy made out a row of low, long flat humps. They seemed like graves in an abandoned graveyard, overgrown with heather and unkempt — no cross or stone to be seen — whose graves could that be?

Tonda halted. "Take it then," he said and held out the knife to Krabat; the boy understood that he could not refuse it. "It has a peculiar property," Tonda said, "that you should be aware of: should you ever be in danger — serious danger — then the blade will turn black as soon as you flick it open."

"Black?" Krabat asked.

"Yes," Tonda said, "Black, as if you'd held it over a candle flame."

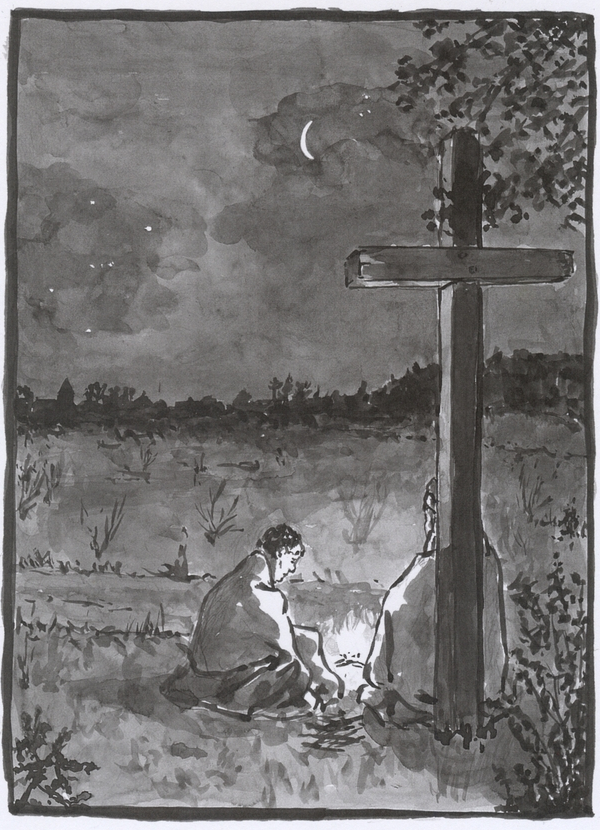

The wake at the cross outside the village, on Easter night, is my favourite scene in the book. It is the will of the Master that the apprentices spend the Easter night outdoors, in pairs, on a spot where someone had died a violent death. In his first year at the mill, Krabat had paired with Tonda, who had taken them to a place with a tall, rough wooden cross, some distance from the village. In his second year, Krabat goes to the same spot with Juro.

Krabat wrapped himself in a blanket and went to sit under the cross. Just as Tonda had sat there a year ago, he sat there now: with a straight back, his knees drawn in, leaning back against the cross.

What I like particularly about this scene is the description of the church bells at daybreak, heralding Easter (because on the day before Easter they are silent), and the girls’ choir starting to sing.

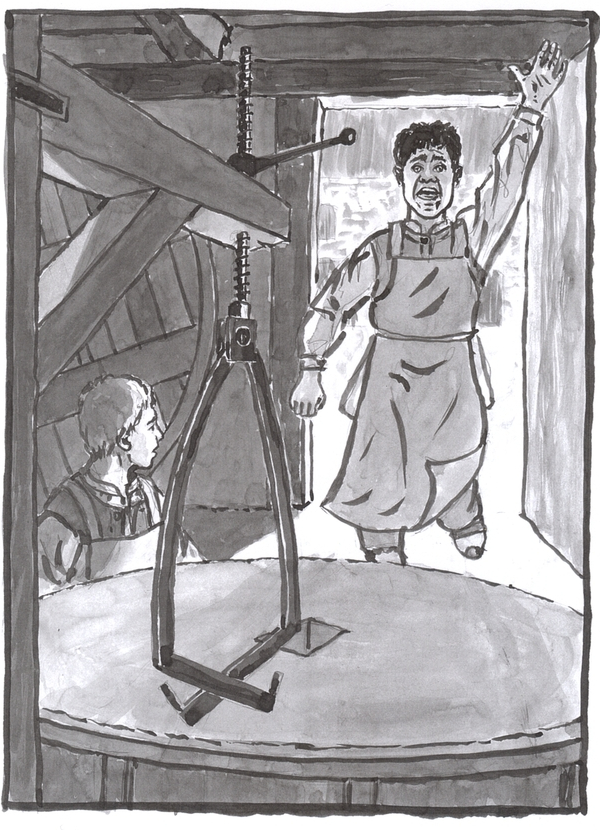

Then there is the scene when Lobosch comes running into the millroom in a panic. Krabat and Staschko are dressing the millstones, an elaborate process that requires dismantling a considerable part of the machinery.

Just when they were about to detach the curb so they could access the stones, the door flew open and Lobosch burst in, pale as death, his eyes wide with fear.

He shouted and wheeled his arms around and seemed to repeat the same thing over and over. The boys only understood what he said when Hanzo stopped the millworks, the mill fell silent and Lobosch could be understood.

"He has hung himself!" he shouted. "Merten — has hung himself, in the barn! Do come quickly!"

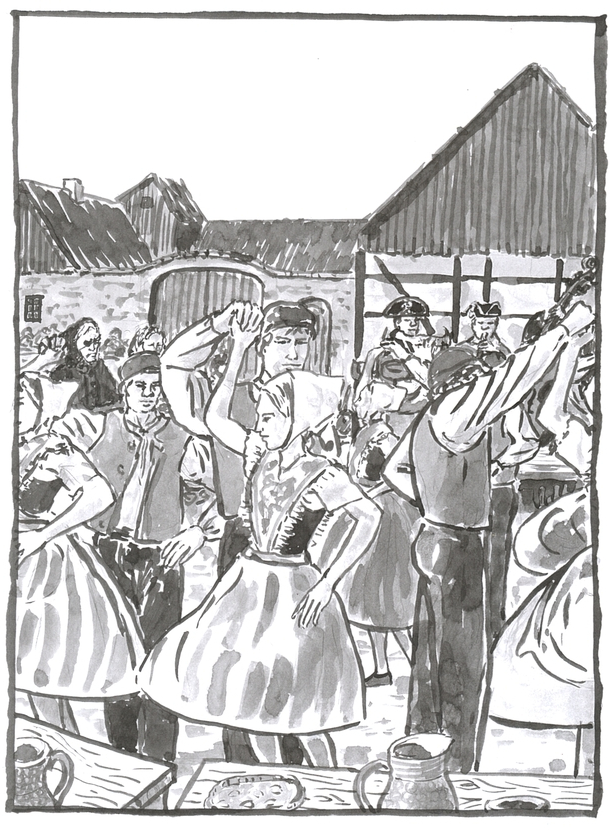

I liked the scene of the village fair because it allowed me to draw the local architecture and the dancer’s traditional dresses. In this scene, Krabat goes and dances with all the girls without choosing, including with the Kantorka, taking care not to give their connection away. I liked this scene

She had understood very well that she should not give herself away. While dancing, they talked the usual nonsense and made jokes and only her eyes showed how she thought about him. Nobody but him noticed it, and when he saw it he quickly looked away. That way even the farmer's wives at their table didn't suspect anything: neither the old woman with the blind right eye (Krabat hadn't spotted her earlier).

Yet it seemed better to him not to ask the Kantorka to dance anymore.

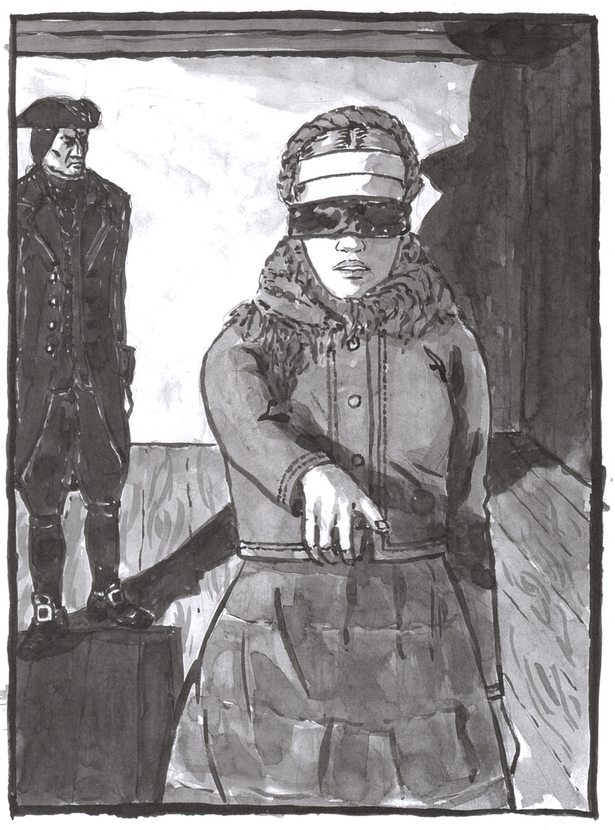

The most dramatic scene of the book is undoubtedly when the Kantorka has to recognize Krabat blindfolded.

From his pocket the Master took a black piece of cloth and blindfolded the girl with it. Then he took her into the room. Krabat started, he had not counted on this. How could he help her now? That way the ring was useless!

The girl walked up and down the row of boys, once, twice.

Krabat could barely keep on his legs. His life was finished, he thought. And the life of the Kantorka too. He was overwhelmed with fear — such a strong fear as he had never felt before. "It's my fault that she must die," went through his head, "My fault ..."

Then it happened.

The Kantorka had walked the row up and down for the third time and now she pointed at Krabat.

"It is he," she said.

"Are you sure?"

"Yes!"

It was over. She took of the blindfold and went to Krabat: "You are free."

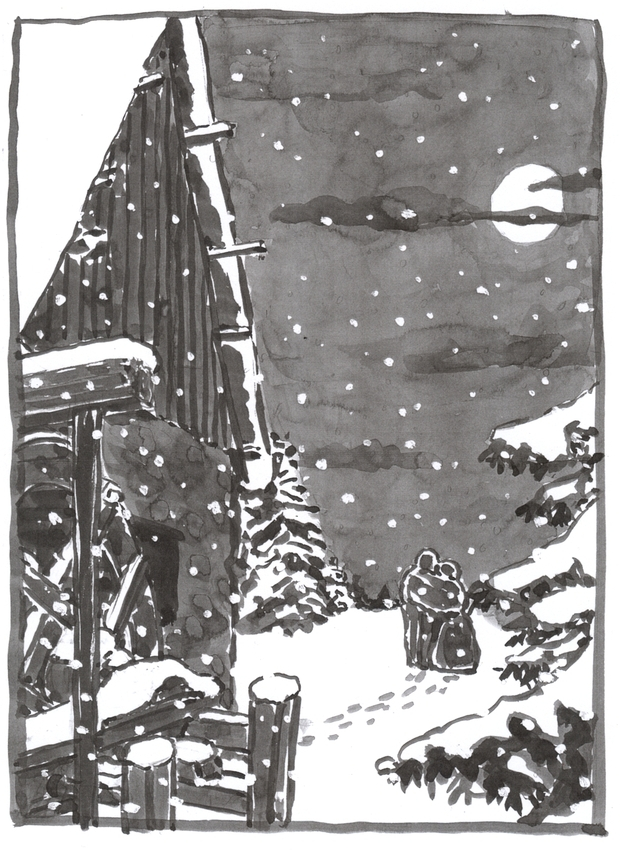

The final scene I illustrated is Krabat and the Kantorka leaving the mill, which will burn down that night. The Master will not see the morning either.

"Let's go, Krabat."

He let her lead him along, out of the mill and through the Kosel moor to Schwarzkollm.

"How did you manage to recognise me between the other boys?" he asked when the first lights of the village appeared between the trees.

"I felt your fear," she said. "You were afraid for me — and that's how I recognised you."

While they walked towards the houses it started to snow, with light, fine flakes, like meal from a large sieve descending on them.